– Trail Dynamics, Stewardship, and the Work Behind the Distance

Like many other ultramarathon events in challenging mountainous environments, Grindstone has never been a race that unfolds without difficulty. Since its first running in 2008, the event has required both runners and organizers to step fully into the rugged and verdant character of the Allegheny Mountains. That character is not uniform but layered: long ascents that stretch patience as much as strength, technical descents that punish inattention, forest corridors where dense foliage obscures distance, and pastoral valleys that remind us of the human life sustained at the edge of the wild. Variety constitutes the texture of Grindstone, and it ensures that each race distance in its current iteration is distinct yet bound together by the same mountain environment.

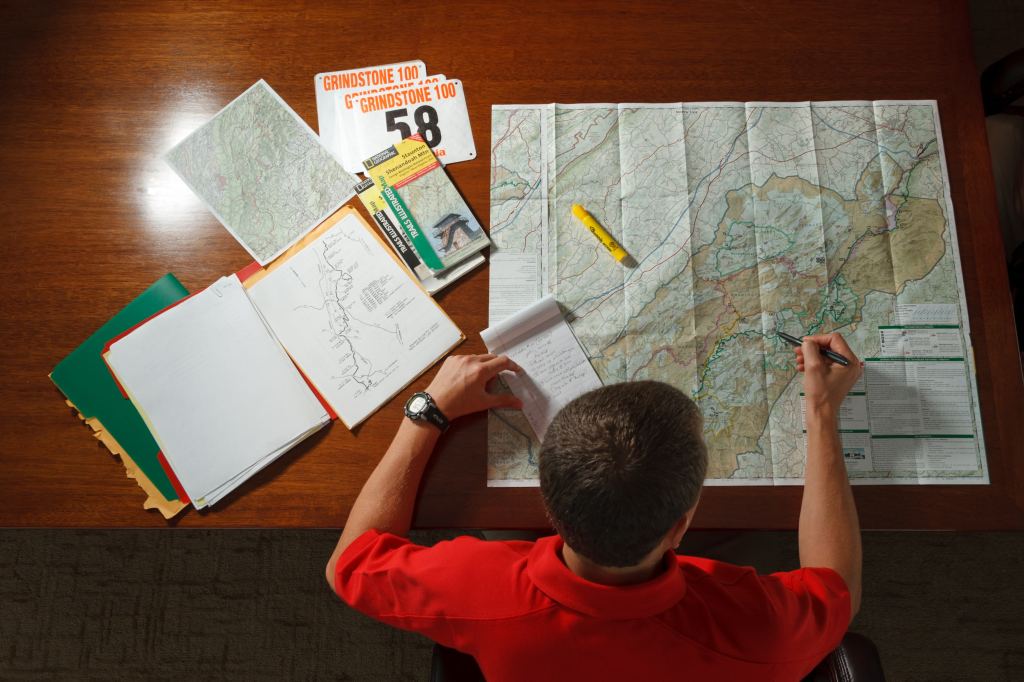

To recognize this variety is also to acknowledge the work behind it. Trails are never static. They shift with storm, season, and use, and they require sustained care in order to remain passable. Every mile of Grindstone reflects not only the natural and cultural ecology of the Alleghenies but also the collective labor that prepares it: volunteers cutting back overgrowth, removing blowdowns, repairing eroded segments, and taking extreme care to mark intersections so that the way is clear even when fatigue dulls awareness. These efforts make possible what would otherwise remain inaccessible. Research increasingly demonstrates that organized trail events, such as Grindstone, play a vital role in keeping trails open, particularly in areas that receive limited visitation. Far from causing harm, they often have a net-positive effect on both the trail system and the surrounding environment (see Trail Impact Study), not to mention the local and regional economies. Grindstone is therefore not only a test of endurance but also an expression of stewardship, linking runners to the unseen work that holds the course together.

For those preparing to race, this also means approaching Grindstone not as a uniform surface but as a sequence of transitions. Moving from pavement to dirt road, from gravel connectors to singletrack, runners must learn to adjust stride and cadence, as well as psychological readiness and expectation. The course demands attentiveness to terrain as much as to effort, and success comes in part from recognizing that the race is constituted by variety rather than monotony. To prepare well is to anticipate those shifts and to understand that endurance at Grindstone is measured not by consistency alone but by the capacity to adapt.

From my Race Director’s perspective, success at Grindstone is therefore never reduced to individual preparation alone. The race is embedded in an evolving landscape of logistics, stewardship, and collective responsibility. Each year brings not only the familiar terrain of the Alleghenies for us, but also new considerations shaped by growth, feedback, and environmental contingency. Course updates and operational refinements (see below) should be read in that light: as modest adjustments that carry significance precisely because they sustain the balance between rugged challenge and responsible care.

Since its beginning, Grindstone has been about caring for trails as much as promoting competition. The race tests runners against climbs, miles, and weather, yet it also reminds us that endurance is tied to stewardship.

To run here is not only to pursue a finish line but to contribute to the ongoing care of the mountains and communities that make such an event possible.

The focus of this blog is to help runners understand how Grindstone’s course is shaped by both natural conditions and human care. From surface variety to trail stewardship, the goal is to offer perspective that prepares entrants not only for the challenges of the Alleghenies but also for the shared work that makes the race possible. I hope the content of this blog will help you better understand what to expect and prepare more fully for your own Grindstone journey.

2025 Course Updates and Enhancements

For 2025, the course routes remain the same as last year. The terrain itself offers plenty of challenge, and consistency gives runners a clearer sense of what to expect. Still, a few refinements are worth noting:

- Additional portos placed at accessible aid stations.

- Female-only portos at the start/finish area.

- Trail Sisters approval affirms the festival’s commitment to inclusivity.

- More variety in aid station food, especially for longer distances.

- Increased shuttle service for dropped runners.

- A new spectator guide will help crews and families follow the race.

- Improved on-course signage will provide greater clarity.

- Expanded live music on stage at the Expo basecamp.

- More food trucks and a coffee vendor will serve attendees at the Expo basecamp.

- Start/finish line orientation to showcase Natural Chimneys as a backdrop for photos.

- A UTMB Kids Zone for family-friendly engagement.

- A new post-race food vendor will provide fresh options for race finishers.

Each change is practical in scope yet significant in impact, refining the race experience without diminishing the challenge that defines Grindstone.

While we cannot address every preference or feedback comment, we strive to make thoughtful adjustments each season. Too many large-scale changes at once would be more disruptive than helpful, and our goal is to balance responsiveness with continuity.

Weather, Uncertainty, and Local Preparedness

Last year’s storms were a clear reminder that no outdoor event unfolds entirely under human control. Severe thunderstorms swept through the area, producing the most significant weather event in a decade for Augusta County, Virginia. High winds and heavy rain forced immediate adjustments, from pausing expo activities to extending course cutoffs.

And while the potential impact of unpredictable weather is part of any outdoor event, it is even more so in ultradistance races such as the 100K and 100M. Over extended hours and multiple nights, conditions can shift: sun to storm, heat to chill, calm to wind. To endure well is not to avoid or despise these moments but to accept them as part of the experience. It is important not to let poor weather conditions taint your race or overall experience, but to recognize them as elements that reveal endurance in its fullest sense (#sufferbetter is what comes to mind).

Over the years, Grindstone has seen both sides of this reality. Some years have unfolded under clear skies and cool autumn air. Other years have brought the opposite, including a one-week delay caused by a hurricane and even a full cancellation during a federal government shutdown. While we hope for calmer skies this September, preparation cannot rest on chance. Our partnership with local emergency management remains central, providing the capacity to respond quickly when conditions shift. Their readiness and capability, together with the adaptability of staff and volunteers, remains central to the event’s backbone. For Grindstone, unpredictability is not an interruption but a defining feature of endurance, and learning to embrace that reality is part of preparing well for the journey.

Trail Work, Permitting, and Stewardship

What happens underfoot on race day is only possible because of the work that continues year-round. For eighteen years, Grindstone has relied on sustained investment in trail care. This season alone, volunteers have logged more than 800 hours and cleared over 65 miles of trail, and that effort continues up until race week. Taken over the life of the event, the scale is even more striking: roughly 1,200 hours of volunteer work each year, multiplied across two decades, amounts to well over 20,000 hours devoted to keeping these trails race-ready as well as open and accessible for all who seek them.

The North River Ranger District of the U.S. Forest Service contributes critical support, particularly in removing large blowdowns. We also work alongside the Shenandoah Valley Bike Coalition, whose members maintain many of the same routes.

Stewardship in the Alleghenies is not divided by sport but shared as a common trust, and organized events such as Grindstone often help ensure that trails remain open in areas where visitation would otherwise be low. Far from being a burden, I believe the race generates momentum for long-term care.

Permitting further shapes the course. At times, this requires sections that fall outside a race director’s preference for a continuous and pure trail experience. One example is Ramsey’s Draft Wilderness, a federally protected area established under the 1964 Wilderness Act and managed today as part of the George Washington National Forest (see U.S. Forest Service, Ramsey’s Draft Wilderness).

The Act limits group size and prohibits organized events of any kind within its boundaries, which is why the Grindstone 100-mile and 100K courses include the gravel road section between Magic Moss Aid Station and Camp Todd Aid Station. No groups larger than ten should ever be in a designated wilderness area. These constraints are not obstacles but reminders. We choose to honor both the letter and the spirit of the law, recognizing that to run here is to respect the legal frameworks that safeguard wild places.

Course marking and cleanup are also collective responsibilities. We have the best volunteers and they give their time to make the route clear and to restore it after the event, though an occasional ribbon or sign may be missed.

In a race of this scale, perfection is neither possible nor the true measure of care. What matters is the shared willingness to step in rather than stand back. We ask runners, too, to take part in this care. Picking up debris, adjusting a misplaced marker, or lending a hand along the way affirms that Grindstone is sustained not only by organizers but by its community. To critique from a distance is easy; to contribute on the ground is harder, yet it is that work which ultimately makes the experience possible. The event is therefore both a competition and a form of stewardship, extending the life of the very trails that sustain us all. Its continuance is a beautiful thing when cared for, inviting runners from around the world to share in the rugged beauty of the Allegheny Mountains and the hospitality of the surrounding communities.

The work of trail care and course cleanup extends directly into how the route is experienced on race day. Markings are placed with care and intention, yet no system is immune to wind, weather, or human error.

At times, it is even more deliberate: unfortunately, it is not uncommon for our Course Director to deal with sabotage, as individuals remove or tamper with markings. His crew responds by covering the course repeatedly, double- and triple-checking critical intersections to reduce confusion. The U.S. Forest Service law enforcement team also provides valuable support, helping safeguard the integrity of the route. What matters most, however, is the runner’s attentiveness, knowing that markings are there to guide but not to replace awareness. In this way, navigation becomes part of the shared responsibility as well, linking volunteers’ preparation with each runner’s capacity to read the course and move wisely through wild country.

Reading the Course and Following Its Markings

Survey feedback often reflects a simple truth: expectations are shaped by geographic awareness and sense of place. Runners accustomed to open terrain may find Allegheny/Grindstone trails dense, enclosed, and at times disorienting. For that reason, the course is marked heavily and intentionally, with redundancies built into the system. Even so, no runner should continue for more than a quarter mile without confirmation. If markings are unclear, backtracking is always safer than assuming. Course markings are meant to support, not to replace, attentiveness. Headlamps in the night, fatigue late in the race, or the distraction of company can make it easy to miss a ribbon or turn. Success here requires as much vigilance in navigation as in pacing.

Likewise, beauty here is not measured only by alpine ridges or sweeping vistas, as it may be in above-treeline landscapes around the world. In the Alleghenies, it is found in hardwood corridors where the canopy filters autumn light, in layered ridgelines that unfold gradually, in mossy drainages that carry the memory of storms, and in pastoral approaches that link mountain to valley.

The colors of fall, shifting by the hour and the ridge, further remind runners that the landscape is alive and changing. Hence, to run Grindstone is to embrace a broader definition of trail beauty: one that privileges variety, subtlety, and texture as much as grandeur.

The character of Grindstone is, moreover, not defined by a single type of trail but by the shifting mix of surfaces that runners encounter. Pavement, gravel, dirt, and singletrack each appear in measure; at times they are welcomed, while at other moments they must simply be endured. Nevertheless, they remain integral to the larger design. To recognize this variety is, therefore, to prepare for it, and to see in it not a distraction but part of the race’s distinctive texture.

Surface Variety Across Distances

Each course includes a blend of paved, gravel, dirt, and singletrack surfaces. This mix is not incidental; rather, it reflects both the geography of the region and the logistical requirements of connecting a race of this scale to the National Forest. In this part of the Appalachian Mountains, there are few venues capable of accommodating the volume of runners that a UTMB World Series race attracts. Natural Chimneys Park is uniquely suited for this purpose, offering both the space for a festival atmosphere and proximity to miles of great trail running, even if it sits a short distance from immediate access to the National Forest. Since no facility in the area backs directly against forest boundaries, connectors provide the necessary link into the forest. Consequently, every distance carries its own distribution of terrain, and runners must adapt accordingly.

21K Overview

- Paved: ~6 miles

- Trail/Dirt Double Track: ~7 miles

Although the shortest race carries more road by proportion, it nonetheless offers a clear introduction to Grindstone’s climbing profile and serves as an ideal entry point for those new to trail racing.

50K Overview

- Paved: ~6 miles

- Dirt/Gravel: ~7.5 miles

- Trail: ~19 miles

The 50K weaves together extended trail sections and dirt-road connectors. As such, it demands attentiveness to shifting terrain and rewards those who maintain rhythm across changes in surface.

100K Overview

- Paved: ~6 miles

- Gravel: ~12.5 miles

- Dirt Double Track: ~7.5 miles

- Trail: ~39 miles

The 100K course is weighted toward singletrack, yet the inclusion of gravel and double-track sections requires runners to adapt continually as the terrain shifts. These connectors are not incidental; they are shaped by both geography and land management, reminding runners that Grindstone is defined by transitions as much as by climbs and descents.

100M Overview

- Paved: ~6 miles

- Gravel: ~15 miles

- Dirt Double Track: ~17 miles

- Trail: ~66 miles

The flagship race remains predominantly singletrack, but transitions test a runner’s adaptability as much as their endurance.

In sum, the distances reveal that no part of Grindstone is one-dimensional. Each race requires runners to adjust stride and mindset continually. For those preparing to toe the line, this means training across multiple surfaces, planning gear that can handle variability, and pacing with adaptability in mind. Indeed, the strength of the event lies in this very variety, which constitutes both the rhythm of the race and the identity of Grindstone itself.

A Collective Effort

In conclusion, Grindstone began as a race, a 100-mile test of patience, strength, and resolve. Over time it has become something more: a festival with multiple distances and a place in the global UTMB World Series, yet still grounded in the same community, ecology, and ethos that shaped its beginnings. To participate is to join a shared labor, one that includes clearing trails, marking courses, delivering aid, and carrying forward a tradition of endurance rooted in care for place and people.

When you toe the line in September, you step into more than a timed competition. You step into an ongoing work that preserves trails, sustains communities, and invites runners from around the world to discover what it means to endure in the Alleghenies. The race is, at once, competition and collaboration, personal challenge and collective stewardship. I am convinced its future will be sustained not by any single effort but by the willingness of many to contribute. The best way to sustain the ultra and trail community is to be an active participant in that shared work, and we invite you to join us in carrying Grindstone forward while strengthening the future of our sport.

This post is original content created by Compass & Cause, LLC. No part may be reproduced or shared without written permission. © 2025 Clark Zealand. All rights reserved.